First, Welcome to the forum, glad you are participating here.

Okay, because of some recent threads I feel I must start with a disclaimer:

Most of you guys know enough about me to know, or at least I will tell you my motive in this question, that I am not trying to condemn, criticize, belittle, or start a major disagreement argument with what I am about to ask. I want to get some 'personal opinions' to help me and hopefully the OP even though his situation has been handled for the time being.

Now, if I saw his post right (I have been up for 30 hrs on a job already, might have my eyes too far closed to be asking this), he said water was 'dripping near the weld area' (note this is not in quotations) and was 'splashing droplets into the weld area'.

Then, from what I gather, he is on a structural job with 2" plate CJP weld. I am ASSUMING (yeah I know what it means) that he is dealing with Category B steel (Table 3.2 of D1.1) which requires at least a 150*F pre-heat and interpass temperatures.

Now, remember too, I am in AZ (rain, moisture, what is that? Does not compute) and seldom have to deal with this scenario but now that it is being asked, I would like to increase my understanding somewhat.

So, with that background here is my question: At what point do you say, 'With the pre-heat and insignificant amount of moisture, that should be evaporating with the heat of the members and the approaching heat of the molten weld metal pool, that it is within safe perameters to go ahead and weld.'? We are not talking about a drenching water coverage from what I understand, and even it he were, for my sake, let's say we are not. We are talking about no more moisture than a man's sweat dripping down into the weld area on a hot day on the TX gulf. OOPS, let's not get personal, LOL.

What I saw in the OP question, and am asking for myself, is such a miniscule amount of moisture that the pre-heat should be dissipating it. Now, I am not trying to justify welding under conditions that will cause improper weld completion. But how 'legalist' (if you will) do we get with some of the conditions. I would think there is a degree of common sense with some things.

I went through D1.1 sections 3, 5, & 6 & the Commentary; D1.8; AISC 341 trying to see if I could find anything further on this. Especially since the seismic codes do add several condition requirements to the welding process and/or environmental conditions to improve the quality, consistency of quality, etc. (wind speed on gas sheilding processes for one). But the only references I found were the same ones that Marshall already quoted.

So, again I ask, how perfectly 'DRY' does the weld area have to be? Do we have studies that will back up these claims? Again, I am not talking about standing moisture or even a steady rain. We are talking about splash droplets from drips to the side of the weld area on preheated steel being welded on.

Please, comments, opinions, clarifications. Just don't throw me under the train.

Have a Great Day, Brent

Brent,

Actually, good points. Metalurgically and mechanically I cannot see water splashing "near" the weld doing squat (with due consideration that it may not only be "near", it may be in as well-how would you know?). The biggest beef is that its poor practice. Which is predominantly why I thought a UT would be sufficient. Though there can certainly be some argument as to the timing of the UT.

In order for moisture to be damaging it has to dissociate in the arc and become part of the weldment which will then evolve through the microstructure and become trapped creating pressure that can induce delayed cracking (that to my knowledge is the current theory anyway-many experts admit they don't really know what the hell is going on). Surface splash will not dissociate or evolve through anything except maybe dirt

However, as mention above, I can see where additional splash could enter the puddle or be located in the bead track to then become a part of the weldment.

If you assume none made it into the weld, then your point is well made.

Brent, I would venture to "guess" that these droplets, no matter how few, presented a challenge to prove that the welds were still satisfactory, so they opted the least expensive route by cutting it out and rewelding, rather than trying to prove it was OK through extensive testing.

I have a hard time convincing my-uneducated, nonmetallurgist-self that it mattered, but non-the-less, when presented with a challenge to prove that the joint was not compromised...I'd vote to cut it out too.

Preheat helps drive out moisture due to evaporation(when it is above 210°F and we are only talking about 150°F), but it also opens the grain of the material to some extent, so I'm not certain how much effect at a molecular level this has with trapping or releasing hydrogen within the grain. Some of you that deal with the super-duper microscopes can probably tell me if I'm all wet or not.

edit: js55 must type faster than me....

John,

I type really fast.

And then correct my typos really slow.

I think I would have opted for a bakeout and a UT scan after some predetermined time. We have phased array readily available.

There is nothing wrong with the choice the poster made, of course, but it is conservative, and expensive.

I sure hope them folks who weld under water don't read any of this ":-)".

Is that a fly I see sittin in the ointment?

maybe.....

Thats a monatomic fly. Thats the dangerous kind. It gets down in the ointment. As opposed to the diatomic type which just sits there.

Better use some of this then.....

Ummmm, is this thread going to the .... FLIES. Sounds like a welding 'horror' movie.

Thanks Guys, especially for the 'Tone' of the responses. What a relief, but nothing less than I expected from you guys.

Yes, I agree, especially as we were not there, they probably made the safest, quickest at the time, cheapest in several aspects choice. If there had been several welds in question it may have been a different story.

I did take notice of the comment, and IF IT HAD BEEN NOTICED BEFORE ANY PROBLEM COULD HAVE TAKEN PLACE, Just get the area protected, use the torch to heat it up and evaporate off the moisture, then continue welding. Apparently that wasn't an option for the OP but a factor to be kept in mind for other occassions.

And I believe your responses matched with my feelings about the moisture, but also agree that bad practices need to be considered. And, if you let the fab shop get away with a little, they will wonder why you stopped them with just a 'LITTLE' more moisture. What a battle.

I just wanted to pursue for some more information. Thanks.

Have a Great Day, Brent

The existence of underwater welding doesn't mean that you can freely pour water into your supposed-to-be-dry weld. (Not that I'm saying the present discussion is about "pouring" water.)

Hg

I'll chime in on one thing that comes to mind here.

J notes that water disassociating in the arc column is likely the bigger issue when it comes to rain type moisture.

If the process is SMAW and the water is splashing onto the weld than I think we can assume it is also splashing the hygroscopic stick electrode flux eh? This would be a vector to transmit moisture into the arc column where it would likely disassociate into Hy and Oxy and quickly move to the weld puddle which is always thirsty for Hydrogen.

A number of the bad things Hydrogen does to steel may happen some time after the weld is completed, so I can see how a cutout is reasonable rather than NDT.

I'm glad not to be the decision maker that has to make big decisions like cutouts after little drops of water go where they are not welcome. The "how much is enough" moisture to cause trouble question is a really good one..... I hope we hear more about it from the other posters.

I have to ask, because I don't know: How long does a dry rod fresh out of the oven stay "dry" in drizzly or misty conditions?

Do the "moisture resistant" electrodes stay dry a few minutes longer?

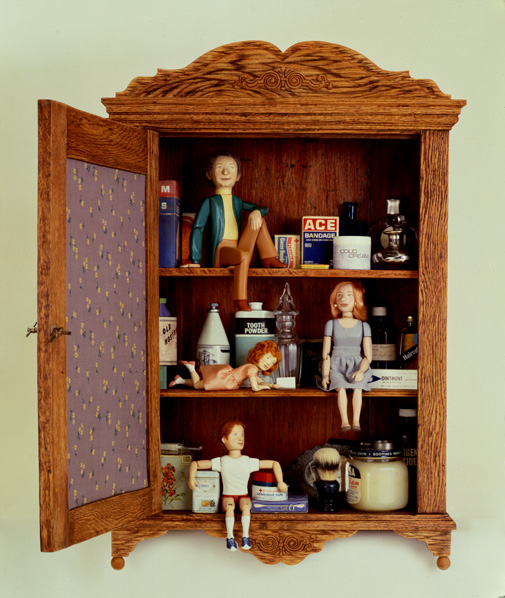

John, I don't even want to know what may be lurking in your medicine cabinet at home. :)

BTW, the silly images were a light attempt to lighten the mood around the forum...hopefully the OP will not get upset at me for going off on a tanget.

A few drops of water, a torrent, or underwater welding. A drop or two to one person is a lot to someone else. The problem with working with humans is the process of "if a little is OK, then a lot is OK.”

Underwater welding is a challenge and one of the challenges is the introduction of hydrogen into the weld puddle by the disassociation of the water surrounding the arc. One solution is the use of austenitic electrodes when welding underwater. The weld deposit is less susceptible to the affects of hydrogen.

Following that line of reasoning I would be tempted to tell the contractor what his is attempting to do, i.e., introduce his welder to underwater welding by introducing minute amounts of moisture into the weld zone, he should be using E309 filler metal. Next, I would bring in a diving mask so the welder could get used to wearing one while he welds. If nothing else it should break the tension in the project meeting where this issue is being discussed.

Rarely do we work in ideal conditions. We should endeavor to optimize those conditions conducive to making good weld. Unfortunately there is the ever-reoccurring problem of the human element. All too often the thought process degenerates to "I got away with it last time; I should be able to get away with it this time." That leads to "There was a little bit last time, I should be able to get away with it this time even if there is a little bit more this time." That leads to "It doesn't make any difference, I do it this way all the time."

I have no solution to this situation since I do not know all the conditions involved. However, there are ramifications to consider, many of which have been touched upon already. It becomes a matter of magnitude. A drop or two is not a problem, a trickle becomes more of a concern, a torrent is a sure sign there will be a price to pay. I have seen contractors argue the point of when is it "really raining?" Dummies abound and thrive, after all, "welding isn't rocket science." As long as that sentiment survives, there will be work for all of us.

Best regards - Al

I just threw the under water welding just to be kind of a Devils Advocate.

All things considered, water is not a recommendable element in your welding process but was it in the weld? Seems to me if the water was splashing into the puddle the welder would have been doing the objecting (complaining) himself.

Can’t imagine it going smoothly with water trying to put out your light. On the other hand, if it was landing on completed weld metal that was still very hot it would evaporate instantly before any Hydrogen could penetrate but it may quench the work to rapidly there by causing problems.

Ether way it really isn’t something to just pass over, it should be reworked or NDEed to show reason not to.

Thanks Al and Ron, I know your answers fit into my additional scenario and helped me and they appear to be right in line with the OP situation as well.

Hope everyone's New Year is going well. Ours is starting a bit better than last year finished off.

Have a Great Day, Brent

Thank you all for all the comments on this. I was aware of how the various AWS / AISC code sections address the topic of moisture and welding. I was looking for more information along the lines of the entrapment of hydrogen in the deposited weld metal and the level of concern that the droplets of water should be. I was also looking for additional information of actual droplets of water vaporizing on the weld during placement and the relation to the concern of hydrogen with low hydrogen SMAW electrodes and the difference of how hydrogen would be induced into the weld. The decision to remove and replace the weld by the EOR was based completely on a liability stand point. With the fact that moisture of any amount was getting on the weld during placement and was documented with the NCR as a violation of the code, took away any hook for the EOR to hang a hat on. Again a liability issue if the weld was ever to fail. From a practical point of view the weld was probably just fine. But "probably" doesn’t sound too good in a court of law.

Again thank you for all the info.

But "probably" doesn’t sound too good in a court of law

No doubt

build a hooch, and if you dont have a preheat wrap on the weld joints then go buy a weed burner and keep gas bottles near by

If I may, first of all I am not cirticizing the decision. It is a good one, though conservative. But also, the choices available here are not 'cut out' or 'probably'.

As Lawrence rightly pointed out the hydrogen damage often takes some time (this is actually the critical variable), consistent with current hydrogen pressure damage theory, but this was the reasoning behind the bake out which would accelerate this time frame. If you have sufficient documentation and technical justification for time/temp bake out parameters (such as the velocity of hydrogen evolution through the microstructure plus UT/NDE to verify there is nothing existent in the weld) then you have far more than probably.

The other problem/reality here is that very seldom are EOR's welding technical guys, and this lends itself, not to a lack of documentable justification as such, but to a lack of technical knowledge and therefore a conservative decision making process.

Not unlike the difference between Div 1 and Div 2 Section VIII. A more robust engineering process can provide justification for a less conservative decision making process. You can build a pressure vessel that is 10" thick if you want to, but with a little more info you don't have to. And the engineering is sound if done correctly.

Thank you js55. Great comments. I agree that as to the fact that most EOR's (in the structural world) technical knowledge in regards to welding is found to be lacking. This is very frustrating at times. I spent much of the first part of my career involved with ASME pressure vessels and power piping fabrication. And yes much was done to minimize hydrogen entrapment with PWHT and DHT of the welds after welding. Unfortunately, that fact is that the structural world doesn’t have the luxury of time and the tolerance for expensive testing and heat treating to minimize that "probably" factor when the code was simply not followed and adhered to. I do however believe that much time and effort has been spent by individuals that have extensive technical knowledge in regards to welding and the science of metallurgy who have been involved with generating the requirements stated in the various AWS and AISC codes. I think its safe to assume that much time has been spent researching this and various other problems such as this and then finding the best approach to gain the desired product quality and how to achieve that as efficiently as possible with everyone in mind.